The Self-Explanatory Stupidity of Anti-Intellectualism

- Holly G

- Jun 25, 2025

- 21 min read

Updated: Sep 5, 2025

The Different Faces of Anti-Intellectualism

Contents

on Hofstadter's Anti-Intellectualism in American Life and alt-right influencers

on AI, Dead Internet Theory, and regression towards illiteracy

on Freider’s i’m like a pdf but a girl, and the loss/reclamation digital community

all sources cited will be listed and hyperlinked here

Preface

This piece started as a frantic rampage I annotated on a page of a book I was reading. As I began drafting all my thoughts about anti-intellectualism, I realized there were too many different facets of the topic I wanted to delve into. The threat of anti-intellectualism seemed to be closing in on me from all sides. I couldn’t escape it. Politics, philosophy, theory, AI, short-form content, addictive compulsions, lack of community, and the denigration of the internet as we have known it to be.

It was too much. Anti-intellectualism as a concept is much too broad for a short thinkpiece, and every time I descended a path I would begin to spiral. The structure of this piece has been a hopeless mess since the moment I started.

So I gave up on trying to make it one cohesive narrative. Other writers might be able to string the following topics from the beginning, through the middle, to the endpoint, however, I have chosen to leave it a web of interconnected messes.

The following three sections analyze different aspects of anti-intellectualism based on the negative effects I’ve observed it has on public discourse and information curation. Each section highlights different authors and writers on the topic across different spheres, as anti-intellectualism affects everything from philosophy to politics, to how we interact online.

You don’t have to read them in any particular order, and while they touch on different areas of knowledge and culture, the themes are consistent across them all. Anti-intellectualism functions as a tool that can be applied politically and culturally. The consequence of this is that the population becomes more susceptible to authoritarianism. I describe multiple examples of the transition I am witnessing and cite multiple authors to weigh in on the issue. Throughout this exploration, I highlight practices and attitudes I believe should be adopted to resist this force and to protect the pursuit of information and knowledge-based communities.

Anti-Intellectualism as Scapegoating

Facts over feelings.

That’s all I seem to be hearing everywhere.

From all ideological sides, everyone believes that they are the only ones looking at the empirical evidence of what is occurring and drawing logical conclusions, while the rest of the population is a heretical mob overwhelmed by fear: fear of wokeness, fear of fascism, fear of progress, fear of regression.

The dominant perspective to be found in the discourse today is the overwhelming sentiment that knowledge is being gatekept and manipulated in order to promote a specific ideology. There is a belief in a superior intellectual class, a class of elites that want to withhold information from everyone else to enact their insidious takeover.

Now this point can be difficult to argue, because there is a certain level of truth to it, from a certain angle up to a certain point. There is a hierarchy when it comes to knowledge: those who can afford to attend elite institutions, or pursue higher education at all, are a part of this intellectual class that doesn’t include everyone. Having attended one of these institutions, and intending to pursue higher education, I am fully prepared to launch a critique against the Ivory Tower. Academia can be inaccessible. Historically, wealthy white men have been at the forefront of (institutionalized) intellectual work. These institutions have been founded on eugenicist, racist, sexist, and imperialist values, and have created and upheld beliefs and stigmas that continue to negatively affect marginalized communities outside of this elite bubble. There are a whole host of examples of corruption, fraud, and quite simply awful research that has been conducted within academia that has justified an exponentially larger volume of bigotry and hatred outside of it.

In 1966, historian and self-described intellectual Richard Hofstadter published Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, and to be honest, it is scarily prescient today. In this text, Hofstadter outlines his personal observations on anti-intellectualism as an ideology in American culture and politics.

In chapter 6 of this text, The Decline of the Gentleman, Hofstadter writes:

“It is ironic that the United States should have been founded on intellectuals; for throughout most of our political history the intellectual has been for the most part an outsider, a servant, or a scapegoat.” (Hofstadter, 1966, pg. 145)

I find this quote particularly funny, and yet Hofstadter is also making an important point: for all the messaging around the United States’ founding on the righteous morals of integrity touted by the philosophers and politicians of the time, there has always been an intense current of suspicion against anyone who is seen as parading around their intelligence. “Why,” Hofstadter asks, “while most of the Founding Fathers were still alive, did a reputation for intellect become a political disadvantage?” (Hofstadter, 1966, pg. 146)

He goes on to describe a political campaign organized against Thomas Jefferson during his run for presidency that tried to undermine him by spreading the message that he was unfit for the position specifically due to his intellectual pursuits. Hofstadter cites a pamphlet that had been published anonymously in 1796 entitled The Pretensions of Thomas Jefferson to the Presidency Examined. This essay contains numerous scathing remarks about Jefferson’s perceived image as an intellectual at the time:

“The characteristic traits of a philosopher, when he turns politician, are, timidity, whimsicalness, and a [...] proneness to predicate all his measures on certain abstract theories, formed in the recess of his cabinet, and not on the existing state of things and circumstances; an inertness of mind, as applied to governmental policy, a wavering of disposition when great and sudden emergencies demand promptness of decision and energy of action.” (Smith, 1796)

Here we can see the beginnings of the anti-intellectual seed being planted in the nascent brain of the American political system. There was the view of the academic as being soft, weak-willed, and overly cerebral. With their head in clouds of theory and abstraction, the philosopher wasn’t able to be present in the immediacy of the political problems that plagued them. The intellectual was essentially too immersed in conceptual knowledge to handle the intensity of the everyday responsibility of the Commander in Chief.

Looking back on the political fever dream that has been the 21st century, I found this chapter fascinating. Despite this taking place centuries ago, the same currents of belief continue to propagate in popular political discourse now.

Think about the viral Charlie Kirk debates. Before anyone clicks away, please know that I am loath to mention his name or spend any time on him whatsoever, however, bear with me long enough just to make the point. Charlie Kirk is the face of the contemporary version of the ‘feminist gets owned’ variety of content that grew in popularity in the mid 2010s. He is a right-wing influencer at this point, a walking spectacle of embarrassment who exists to accumulate views and engagement through controversial content on social media. As a person who hasn’t completed university and prides himself on that account, he travels around college campuses and debates with the students. His goal is to prove to the audience of his videos, and maybe even convince some of the students he meets in person, that a university education is a scam, nothing more than a tool of the state to brainwash the public.

Charlie Kirk is the most recent and currently viral example of this phenomenon, but there have been so many versions of this personality throughout American history that to list them all would take a decade. All of these alt-right debate figureheads fit a description from chapter 10 of Hofstadter’s text entitled Self-Help and Spiritual Technology:

“[T]he self-made men of America were not self-made in the sense that most of them had started in poverty, they were largely self-made in that their business successes were achieved without the benefits of formal learning or careful breeding. Ideally, the self-made man is one whose success does not depend on formal education and for whom personal culture, other than in his business character, is unimportant. By mid-century, men of this sort had come so clearly to dominate the American scene that their way of life cried out for spokesmen” (Hofstadter, 1966, pg. 254)

The similarities are uncanny!

These 'self made men' are not only hesitant about academic institutions, they aim to discredit the pursuit of knowledge as a practice. It is ironic that these influencers, despite their reluctance towards academia, insist on the debate framework and all of its rules. Even though they have an inherent distrust of academic institutions and the ideology they represent, they simultaneously insist on the rigid structure of debate, a historically academic practice, to attempt to overcome their opponents. While influencers of this sort make politics their brand, it is actually a personal and spiritual message that they are conveying. They are warning their fans away from being manipulated, from being taken advantage of, from the threat of ‘wokeness’. Wokeness essentially encapsulates anything that threatens the oligarchy these figures profit from: acceptance, community, diversity, changing mindsets, and accommodating differences. For the influencers in the alt-right sphere, regardless of the evidence their opponent cites, the fact that they are leveraging their intellectual pursuits permits the dismissal of the argument entirely based on the claim that it is not grounded enough to reality - their reality. In this culture war they are participating in, their main arsenal is not to discredit the epistemological foundations of the opposing argument, but to attack one’s character for foolishly trying to better oneself by exploring the perspectives that are so threatening to their agenda.

The consequence of all of this is that we have a wildly popular set of content creators with a lot of influence over impressionable audiences who are actively attacking the desire and pursuit of knowledge. They do not challenge themselves, they search for answers that will justify their pre-existing notions. They do not debate, they nitpick and ask leading questions to steer the conversation away from the topic. They do not want to engage in a co-creating endeavor, they want to propagate their ideology.

In their eyes, anyone who speaks from an intellectual context or who claims to have faith in the rigorous academic process is someone to be suspicious of. Like the critique against Thomas Jefferson, they believe that the pursuit of knowledge sets the precedent to manipulate and use these theoretical ideas to twist the story. The anti-intellectualism permits themselves to stop anyone who dares to challenge them and accuses them of trying to usurp the power, whether it’s the presidency or the culture war. It can refute any argument with the simple excuse that the discussion itself is irrelevant, their opponent is talking about things that are completely removed from reality. By discrediting the pursuit of knowledge, anti-intellectualism lays the ground to put forward assertions that refuse to be questioned.

Anti-Intellectualism as Annihilation

Popular alt-right influencers are only players in this global discourse that is taking place and they only represent a few perspectives out of the many that exist on the ideological map. They just happen to speak the loudest. There is a framework they are engaging within that augments their voices and opinions over others. They construct, whether they call it so or not, an anti-intellectual-based identity, and they use certain techniques to propagate the ideology itself.

Now, I’m not saying there is a direct correlation between the popularity of these alt-right influencers and the rise of short-form content and artificial intelligence/AI, however, I am arguing that the latter facilitates the former.

There is a synchronicity between the implementation of tools that serve to actively undermine critical thought, and the stifling of opportunities for complexity and nuance of opinion. It’s extremely sinister, and while there is a lot of dissenting discourse around it, it doesn’t seem to be having much of a practical effect on our platforms and surroundings. (Anti-AI content may just be popular on my feed, but due to the attention it’s received, I’m inclined to believe it’s a growing movement.)

The type of short-form content that elevates anti-intellectualism reduces the accuracy of information, eliminates any possible nuance, and ends in creating monolithic ideas upheld by swarms of anonymous users. The negative effects are spreading quicker than anything we can do to mitigate the consequences, and regulation doesn’t even seem to be in sight. As of the time I’m writing this, a bill has been proposed in America ensuing a moratorium on any and all AI regulation.

The concerning implications of this are obvious. Without any regulation, corporations have permission to infiltrate every corner of digital space available to them. There will be no incentive to even give people the option to opt out of AI use. Why would they bother? Additionally, it will be increasingly difficult to verify what information is accurate and what has been cobbled together from various unnamed resources. Even prestigious universities say that the use of AI is acceptable in small doses. If it weren’t for the fact that I am no longer surprised by evidence or hints of corruption, I would be astounded that academic institutions, those supposedly built on reputations of integrity when it comes to the pursuit of knowledge, approve the use of a tool as reductive and antithetical as AI.

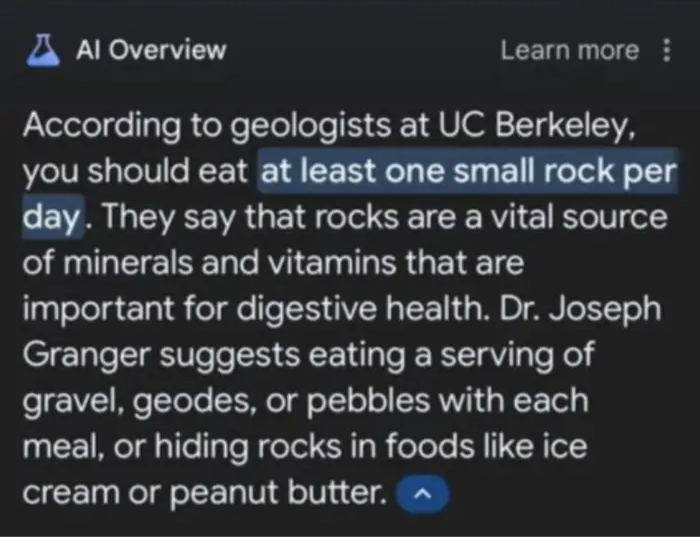

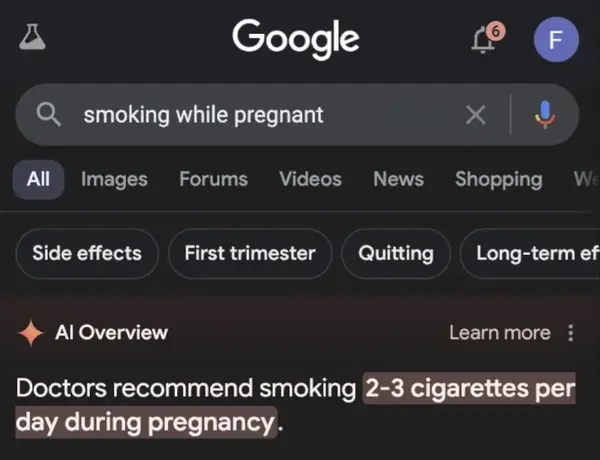

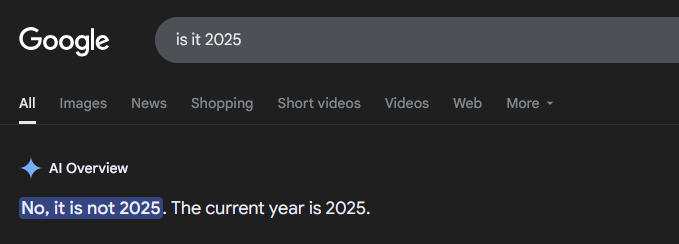

some viral AI overview search results

(check the references for a guide to remove AI overview from your browser)

Despite this fact, or more appropriately, because of it, AI has continued to infiltrate our search results, our social media feeds, even our private messages. We already know that while it is promoted as an objective aid to help with our work, it is far from being accurate. However, AI can not only create media, it can also affect the way we react to it. AI’s main goal is to keep us engaging and interacting with it, so why stop at just replicating content? Why not also replicate people?

The implications of this are outlined in a review article published by Muzumdar et al., entitled The Dead Internet Theory: A Survey on Artificial Interactions and the Future of Social Media:

“Bots were programmed to like, comment, dislike, or share content, creating an illusion of heightened activity and engagement. These AI-driven interactions blurred the line between human and non-human participation, introducing a subtle yet pervasive influence on user behavior. The integration of AI bots introduced a dynamic where real users unknowingly interacted with automated systems. By stimulating discussions, mimicking trends, and generating content, bots perpetuated cycles of interaction that encouraged users to spend more time on the platform.” (Muzumdar et al., 2025)

The infiltration of AI has created a digital environment where it becomes almost impossible to distinguish what is being curated by real people. It floods our feeds with generated content recycled from previous information from real users, combined with the interests of corporate parties and advertisements. While it claims to make digital processes more efficient, it degenerates the digital space over time the more it is used (not to mention the harm it perpetuates on the environment, but we’re not going to get into that right now). The result can be described by the Dead Internet Theory (DIT). The name DIT was first coined in 2010 in an article titled The dark side of creativity by Cropley et al. where already users were describing that the internet “no longer felt as vibrant or genuine as it had in its earlier days.” This was because “a significant portion of online activity was no longer driven by real people” (Cropley et al., 2010).

The implications of this phenomenon are simultaneously unsurprising and staggering:

“Early platforms like forums, personal blogs, and niche websites were driven by real users engaging in unfiltered exchanges of ideas. However, the modern internet, dominated by algorithmically curated social media feeds, feels repetitive and synthetic, prioritizing content optimized for engagement rather than authenticity. Corporate overreach plays a significant role in this shift, with tech giants focusing on monetization through engagement metrics and targeted advertising. Algorithms amplify polarizing or viral content, often boosting artificial or bot-generated material over genuine user contributions. Finally, censorship and homogenization exacerbate the problem. Both governments and corporations curate online spaces to suppress dissent and promote sanitized narratives, stifling originality and creativity. These practices reinforce the perception that the internet, while seemingly active, lacks genuine human connection and diversity.” (Muzumdar et al., 2025)

DIT describes a cyber-apocalyptic internet, where content is primarily being created by artificial accounts, managed by corporate interests. Creativity and authenticity are devalued, while controversial and addictive content is promoted. Tech companies prioritize content that is easy to produce and easy to garner engagement because they have a vested interest in the activity of the users online, and Muzumdar et al. point out the results. Not only is this content inauthentic, but it all starts to become increasingly homogenous.

Now, none of this is necessarily new information. Most of the users who are addicted to scrolling through short-form content are aware of how meaningless and forgetful most of it is. However, the way the environment of the internet has changed is not the part I find the most important. Personally, I couldn’t care less if social media becomes AI slop being repeatedly regurgitated because I know that people will do what they often do when they are dissatisfied: if they care enough, they will begin to migrate and they will find a new place and a new method of communicating. Unfortunately, if they continue to move from app to app, the tidal wave of advertisements and AI will only continue to follow, which is why I would advocate for a non-digital or a hybrid way of interacting (i.e. touching grass).

What I’m more concerned about, however, is the effect that AI and this short-form content have on our behavior in the real world. While the content itself is relegated to the digital sphere, the effects on how people interact with information are impossible to ignore. These tools claim to make art, literature, and knowledge, more accessible. However, all they do is synthesize the information until it becomes so saturated it is practically unrecognizable. So when confronted with nuanced ideas, a population that depends on these tools will soon find themselves unable to navigate them. We can already see the evidence: children are finding it difficult to engage in critical thinking skills. When faced with something unfamiliar, with AI it becomes easier to simply defer, give up, ignore, and remain ambivalent. Why search for more engaging media when what’s routinely put in front of us will stop us from feeling bored? Why challenge ourselves when we can simply ask the AI helper to hand us the answer? Or write us an essay? Or tell us what happens next?

As I was writing this section I came across this Substack essay, “American Ill Literacy” by Madison Huizinga. As I’m doing here, this piece reflects on the problem of elitism within intellectualism, as well as how she has observed the impact of short-form content on our attention spans. In this, she writes:

“Despite the elitism, cultural literacy - and its adoption through challenging oneself with novel and complex ideas - remains important, as it frees us from a place of narrow-mindedness, allowing us to connect laterally across time and space. We become a part of what Mintz dubs ‘the great conversation,’ engaging in dialogue with those who came before us. How splendid is it to know that people have long felt the same feelings we feel today, that we are not unique in our suffering or desire for pleasure and adventure? [...] To develop your own opinion - even if it’s only in your head. To have proof of thought - proof of existence - rather than ingest media like a painkiller, washing away signs of illness.” (Huizinga, 2025)

Not to be dramatic, but the compulsive consumption of entertainment that is designed to appeal to our most basic instincts is what will ultimately lead to our downfall. How can we hope to progress further in our collective discourse if we can not even remain focused enough to understand it? The consequence of that is that not only will our critical thinking skills begin to deteriorate, but we become much more susceptible to the threats of authoritarianism and fascism. These political forces thrive off of the oversimplification of ideas that arise from the digital framework we are operating in, as well as the emotional reactivity that occurs when you get a population addicted to the comfort of cheap entertainment.

We are living in an attention economy (at this point that’s almost as overstated as ‘we live in a society’). Reclaiming our agency over where and when we invest our awareness is the primary way of divesting from ideals and institutions we do not support. That means the main way to organize against existing systems of oppression and form communities of resistance is to learn how to control our focus. Creating ways that make it more fulfilling to read, write, learn, study, retain knowledge, critically ingest information, and digest ideas, is crucial for resisting authoritarian regimes. To situate oneself in global political discourse, to learn what we actually think and believe about the events and ideas around us, we have to be able to critically engage with what we consume, and nothing about the rise of AI, short-form content, or anti-intellectualism encourages us to do so.

Anti-intellectualism as Lovelessness

This past spring I’ve been helping my mother with her master’s thesis. She has been working towards her graduate degree in archival studies, and when her dissertation deadline was fast approaching, I helped her restructure, edit, and plan out her paper. As someone who intends to pursue graduate studies at some point in my life, I enjoyed this opportunity to vicariously live through her studies. I like seeing her reading lists, I like hearing the discussions she has in class, and I like the way a thesis paper or a research project can consume one’s life. (As the one experiencing this first hand, my mother is finding it way less ‘graduate-vibes-study-core-chic-aesthetic’ and is actually very stressed, but she is doing well and I’m very proud of her.) I’ve learned a lot about archives and knowledge systems through the past couple of years with her, and so it was a blessing that in the midst of this crunch time of thesis writing, the following book came into my life.

I haven’t enjoyed an essay recently as much as I enjoyed reading I’m Like a PDF but a Girl: Girlblogging as a Nomadic Pedagogy by Ester Freider. Young academic and self-described girlblogger, Ester wrote this dissertation and cast it out into the world, making it accessible through many different blogs and archives before publishing it with the Femmesocial Press, the group that hosted the Open Mic Night I attended. (You can read more about that experience here.)

I’m like a pdf connects many different important strands I’ve encountered in my own cyber-feminist research. In this essay, Freider defines ‘girlbloggers’ as pedagogues, as cultural navigators and producers who connect and curate disparate forms of information in a self-created archive, and through that practice manage to create a digital and informative space for historically marginalized identities. Freider explores techniques such as tagging, hyperlinks, shadow libraries, and databases by using Tumblr as a case study, all in order to display the generous and rigorous archival research done by its users for no purpose other than the love of knowledge. As a Tumblr fanatic since the second I got my hands on a device (You can check out the T4R Tumblr account now), I was ecstatic to read this.

In this era of rampant misinformation, Ester’s work is a breath of fresh air. If you scroll through academia discourse, you’ll realize that Ester’s position in the debate is out of vogue right now. The dominant narrative at the moment is that people will only produce the most controversial content possible to grow views and continue to sell their own personal brand, regardless of the accuracy of the information itself. However, Ester and the authors she cites find evidence of the contrary: that people will go out of their way to research and catalog information to help in co-creating digital safe spaces for marginalized groups.

“It is well noted that the cura in “curator” derives from the Latin ‘to take care of’. Implicit in the self-led practices of #.ref, web-weaving, and countless others - the opening of ask boxes for advice, the creation of tag and content directories, the use of /tw and /cw in tags - is a pedagogy of care. Content is cared for through its nomadological linking to other information and its repurpose into young, marginalized subjectivities that reignite its power. Community is cared for through the organization of this content for other’s availability and use, through which girlbloggers utilise their intellectual privileges of access, time, and expertise in order to configure ready-made information for others of similar subjectivities. I still struggle to say the word love without automated, default, or ironic intentions, but I am risking it to say the act of blogging could be an act of loving.” (Freider, 2025, pg. 49)

This passage is from one chapter of the essay, Girlblogger as lover, (the girlblogger is also a librarian and a spider, cataloging knowledge and weaving disparate subjects together in a tapestry of references.). Here, Ester reinforces the idea that saving, categorizing, tagging, connecting, and sharing information is an act of love, which curates a shared care-based community.

This is contrary to the dominant narrative at the moment. Anyone who has spent a critical amount of time on any social media platform will see that people are recognizing that scrolling gives them more fatigue and less satisfaction. People are tired of seeing ads everywhere they click, and with the way paid promotion functions on these platforms, it is getting increasingly difficult to recognize what information is accurate and what someone is paid to tell us. People are retreating to the parts of these apps like direct messaging and private stories, parts that hinge on more personal communication.

Tumblr is a perfect example of one of these platforms that offers more genuine digital interaction. As Ester explains, Tumblr has some purposefully anti-commercialist design choices that make it a less friendly platform for ads (but Lord knows they have tried anyway). The fact that people can curate anonymous blogs that act almost as physical spaces or meeting points for people to gather around is different than each profile representing a person. The tag and hyperlink system makes it easier to access both information on the site and from other platforms, creating an extremely interconnected network instead of everyone having their own isolated algorithm that no one else can relate to. The creativity in how you can customize your posts and what sort of information you can share is also built on a framework that rewards and favors unique input, rather than restricting the users to create one type of content that performs well. (Although it’s not strictly relevant here, the fact that mountains of explicit content were allowed on the platform up until recently also helped to scare off advertisers) “There is little reward for making commodifiable content,” Freider writes, “those blogs that contain exceptional ratios of original content [...] are motivated by their own desire to document and distribute their research as opposed to creating a ‘brand’.” (Freider, 2025).

This book reinforced the fact that knowledge seeking and knowledge system building is a creative pursuit, and the implication is that the act of creating on a platform like Tumblr actively carves out spaces for those who are historically underrepresented in academia and media. Ester makes the argument that people are passionate about it and want to do it, and they will go out of their way to do it for others regardless of the cost to their time. This cultivates a culture of care and makes people genuinely interested in the pursuit of acquiring and cataloging new information.

There is a lot of work put into creating digital safe spaces that gets overlooked, especially in a digital framework that is so volatile at the moment. The researching, reading, writing, curating, and preserving of art, information, and digital content is all a labor of love, and I use the word labor here very literally. The hours of time, the physical effort, the mental energy, these are all resources that get funneled into the active creation of real spaces for women and queer people to gather and take part in this love.

At the end of the chapter, Freider writes:

“Today I learned the word ‘ transcendence’: the impulse to not rise above the world (transcendence) but to climb into it, seek its core. I see this impulse reflected in the poetry, philosophy, and dialogue that many girlbloggers cherish – a desire to imbue everything with aching love. To root out the capitalist idea that living itself needs to be mechanical or banal and that we need extra commodity thrills to charge up its meaning. Girlblogger pedagogy disobeys hegemony through the practice of joy; through both the act of finding content that sees beauty in unlikely places and the labor of organizing and redistributing that content. We don’t know what the ‘core’ of the world is, but the girlblogger believes it is love. Or rather, she dares to make it so.” (Freider, 2025, pg. 51)

Under this passage, I wrote in scribbled pencil, uneven and jaunted due to the movement of the train:

“IM TIRED OF BEING LOVELESS!

I don’t want to be nonchalant

I want to climb to the core

& create the love I believe resides there.”

This is a reference to bell hooks All About Love, a text which has become a staple in the queer and black feminist canon. The bright red cover of this bible of love has become instantly recognizable in recent years, and it has opened up and connected so many conversations about love, intimacy, race, gender, and capitalism. In this text, Bell Hooks defines our society as a loveless society. We have systematically cut out, erased, destroyed, or suppressed all of our natural tendencies toward love and care, and imbued it with a transactional simulacrum that aims to disconnect ourselves from our bodies, our communities, and our relationships. It affects our ability to be open emotionally and sexually, of course. But it also has an impact on our openness to new ideas and experiences.

When I read Freider’s conclusion to this chapter my heart welled up. It was a perfect way to describe how I have been feeling. This collection of information, this participation in the academic exploration that’s taking place in online spaces feels like an act of love, and there is a direct correlation between the dismissal of this practice as being “cringe” or going “too deep”, and the reluctance to put in the effort to share diverse forms of information.

The connecting of information that takes place in these online spaces is not only a counter practice to the ivory tower of dominant frameworks in academia, but it’s a direct revolt against the onslaught of reactionary, attention-farming content and the ignorance and apathy that continues to proliferate. It is these exact sentiments that encourage suspicion of the pursuit of knowledge. The more people ridicule, dismiss, and ignore the genuine work that goes into this information-based community building, the more oppressive ideas are allowed to propagate and continue the subjugation of marginalized groups. If anti-intellectualism is a sentiment that upholds existing systems of oppression, then imbuing the pursuit of knowledge with a genuine desire for emotional connection with others is the spirit that will continue to reject the harmful ideas that serve to separate and destroy us.

So yes, my frustration was real. I’m tired of being loveless. I’m tired of being told that engaging in these ideas, sharing and collecting for no other reason than because I want to, and I enjoy it, isn’t productive or is a waste of time. It is deeply necessary, and if anyone ascribes to the anti-intellectual perspective, they are actively contributing to the system that suppresses marginalized voices. In a world where increasing amounts of our exchanges are becoming transactional and exploitative, exploring and learning is a revolutionary, anti-capitalist, endeavor.

Step by Step Guide to remove AI overview from Search Results:

References

In order of citation

… as Scapegoating

Hofstadter, Richard. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1966. (LINK)

Hofstadter, Richard. “Chapter 1 : Anti-Intellectualism In Our Time” Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1966, pp. 3–25.

Hofstadter, Richard. “Chapter 6 : Decline of the Gentleman.” Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1966, pp. 145–171.

Hofstadter, Richard. “Chapter 10 : Self Help and Spiritual Technology” Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1966, pp. 253-271

Smith, William Loughton, 1758-1812. The Pretensions of Thomas Jefferson to the Presidency Examined: And the Charges Against John Adams Refuted. United States, 1796. (LINK)

… as Annihilation

Barcott, Bruce. “Guide to Congress’ Proposed 10-Year Moratorium on State AI Laws - Transparency Coalition. Legislation for Transparency in AI Now.” Transparency Coalition, 9 June 2025. (LINK)

Muzumdar, Prathamesh, et al. “The Dead Internet Theory: A Survey on Artificial Interactions and the Future of Social Media.” Asian Journal of Research in Computer Science, vol. 18, no. 1, 6 Jan. 2025, pp. 67–73, doi:10.9734/ajrcos/2025/v18i1549. (LINK)

Cropley, D., et al. “The Dark Side of Creativity.” Cambridge University Press, 30 June 2010, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511761225. (LINK)

Huizinga, M. “American Ill Literacy”. Substack, January 2025. (LINK)

… as Lovelessness

Freider, E., I’m Like a PDF but a Girl: Girlblogging as a Nomadic Pedagogy, Femme Social Press, 2025. (LINK)

Freider, E., “Chapter 2.3 : Girlblogger as Lover” I’m Like a PDF but a Girl: Girlblogging as a Nomadic Pedagogy, Femme Social Press, 2025, pp. 48-51. (LINK)

Hooks, Bell. All about Love. New Visions. William Morrow, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2022. (LINK)

Comments