Pleasure Activism as a Tool of Resistance

- Holly G

- Oct 10, 2025

- 20 min read

Contents

Introduction

When the state of the world seems too overwhelming, when it seems as though there is nothing else to be done other than lie down and bedrot into oblivion, it can be a struggle to find some grain of hope to hold on to.

Everyone has to find their own reasons to keep resisting, to continue to organize, to persevere in defying oppressive institutions. One thing that helps me to keep moving forward with integrity is to have a philosophy that inspires me with an ethos that can be applied to different areas of my life.

adrienne maree brown’s 2019 text, Pleasure Activism: the Politics of Feeling Good, is a source of that philosophy for me.

“Pleasure is not one of the spoils of capitalism,” adrienne maree brown writes on page 16, “it is what our bodies, our human systems, are structured for.” In a later chapter, she continues this thought: “We had jobs, we had oppressions, but the center of our lives was pleasure, celebration, dancing, music, cooking together, sharing a critique of our country, seeking freedom in the here and now.” (pg. 238)

The central argument that is so compelling to me, is that it offers opportunities for direct action, and restores agency within individuals to participate in a larger movement. These things often feel so far away when it comes to experiencing anxiety in the face of the world’s suffering.

Pleasure Activism is the radical self-care that must take place after experiencing or witnessing a hate crime. Pleasure Activism is the difficult, vulnerable work of freeing your queer relationships from addiction and shame. Pleasure Activism is thousands of people dancing in the streets despite police forces trying to surround them. I agree with fellow and previous Black Feminist Theorists who believe this philosophy is deeply necessary to resist systems of oppression. And so I want to share the pleasure we are capable of feeling.

What is Pleasure Activism?

In preparation for this post, I wanted to give a summary of Pleasure Activism for those who were not as familiar. It is available to see here on the T4R Instagram page.

Essentially, Pleasure Activism is an approach to activism that centers on the pursuit of pleasure as an act of resistance. This is especially relevant for oppressed groups who have historically had their agency revoked from them. The pursuit of pleasure is one of the clearest reinforcements of one’s humanity, as one is pursuing desire, pleasure, fulfilment, and satisfaction in life.

These values have always been seen as integral human rights: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” (United States Declaration of Independence, 1776) However, when it comes to oppressed and disenfranchised groups, they have often been seen as privileges or exceptions. Restricting these values is a form of dehumanization. Therefore, reclamation is a form of resistance against oppression.

Pleasure Activism is inspired particularly by Audre Lorde’s essay Uses of the Erotic. This is a seminal piece in Black Feminist Theory and one of the foundational texts of Tools for Resistance. The Erotic, while specific in this case as an example of resistance towards the intersection of misogyny, queerness, and racism, actually encapsulates a force that can be used to resist all forms of oppression. The Erotic that Audre Lorde describes in her essay is defined as: “... a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling. [...] But the erotic offers a well of replenishing and provocative force to the [person] who does not fear its revelation.” (Lorde, Uses of the Erotic)

The Erotic can be difficult to understand at first. Partly because of the term itself can be easily misinterpreted and partly because of the elusive way in which it can be expressed and transferred. But if you identify with what Lorde is describing, you know it is a sensation that, once it is felt, cannot be ignored.

To help orient us around what the Erotic is, and thus what Pleasure Activism is, we can use what Audre Lorde describes as the functions to guide us:

“The erotic functions for me in several ways, and the first is in providing the power which comes from sharing deeply any pursuit with another person. The sharing of joy… forms a bridge between the sharers which can be the basis for understanding much of what is not shared between them and lessens the threat of their difference.”

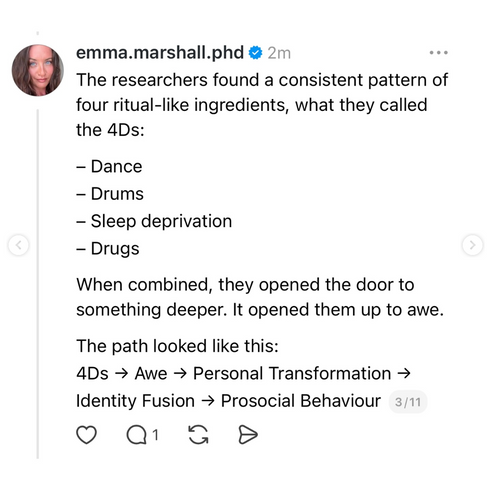

The first function of the Erotic is not just the experience of pleasure for the individual, but the connection it creates between people. When you are engaged in a pleasurable experience within a group or community, it is more likely to extend empathy towards those people, regardless of commonalities you do or do not share with them. The threat of distance, the false barriers, and the gaps of understanding are, arguably, what generate the most fuel for hatred and ignorance. As those gaps narrow, it is easier to extend one’s empathy, labor, time, and resources towards the other.

This offers an example of joy and celebration in generating prosocial behavior, empathy, and collaboration

This is particularly pertinent for me when it comes to collaborative endeavors in organizing, arts, or at work, especially when you are working with people that you are (supposed to be) at odds with. Unnecessary competition is often injected into our interactions with each other, even within our ingroups, not just those across spectrums or borders. This is to create more conflict within communities to distract from those who ultimately benefit from our inability to collaborate. The more we see and understand each other, the less our differences are a threat to one another. Thus the more likely we are to recognize those who are much more dangerous to our collective well-being.

“Another important way in which the erotic connection functions,” Lorde continues, “is the open and fearless underlining of my capacity for joy. [...] [T]hat deep and irreplaceable knowledge of my capacity for joy comes to demand from all of my life that it be lived within the knowledge that such satisfaction is possible, and does not have to be called marriage, nor god, nor an afterlife.” (pg. 31)

This function, the recognition of the joy we are not only capable of, but that we deserve, is especially radical when applied to the value of labor in our current society. Most work today has been transformed into, as Lorde describes, a “travesty of necessities”, and it swallows our whole lives. It is not new or unique to engage in discourse on how work, from the 9-5 performance to the monotony of minimum wage labor to the indentured servitude of populations in the global south, has become increasingly extracted of the value that can be bestowed on the individual, and the benefit that it can provide for one’s own family and community. This has taken place largely through the devaluation of labor itself, and thus work begins to eclipse all other facets of life, such as social and cultural values.

By imbuing our work with the Erotic, the potential we can recognize within all of us, it is essentially a path to radicalization, as we discover that we need and deserve more from our labor than what we have been told we can receive. We deserve labor that we find fulfilling. We deserve work that is valuable to our community. And moreover, this applies to where we live, how we move through our cities and nations, how we interact with people within and outside our society, and the time we spend individually. Through the Erotic, we become less susceptible to the messages that continue to tell us that it is only possible to experience that fulfilment after a certain amount of time or labor has been extracted. Once we acknowledge the joy we are capable of feeling, Lorde argues, we must demand that from every part of our life, and thus we begin to seek liberation for ourselves and everyone around us across all facets of life.

“This is the reason why the Erotic is so feared… For once we begin to feel deeply all the aspects of our lives, we begin to demand from ourselves and from our life pursuits that they feel in accordance with that joy which we know ourselves to be capable of. [...] For as we begin to recognize our deepest feelings, we begin to give up, of necessity, being satisfied with suffering and self-negation, and with the numbness which so often seems like their only alternative in our society. Our acts against oppression become integral with self, motivated and empowered from within.” (pg. 32-33)

This is an idea that deeply informs my approach to activism. Whenever I feel that I am at a loss for what to do, or I feel as though I am powerless, or like there are no options left, I return to this sentiment.

What Pleasure Activism is Not

A lot of the work that is displayed in the ‘work’ section of T4R grapples with some of the arguments and contradictions within Pleasure Activism. It extends across different areas of knowledge, but all share an element in common in that it is attempting to reinforce the philosophical and political arguments in favor of Pleasure Activism. I will use some of this work to explain a bit more of what Pleasure Activism is not in order to clarify the parameters of the ideology.

PA is not overindulgence

One of the most common critiques of Pleasure Activism, which is actually based on a misinterpretation of the idea and what it represents, is that it is somehow advocating for unbridled indulgence.

Extract from “The Power of Pleasure Politics: Reconstruction and critical assessment of the racial justice capabilities of Pleasure Activism” by Holly Gregory (2023)

In the Pleasure Activism section of this page, you can find the summary and deconstruction of a paper that I wrote that engages in a philosophical investigation of the liberatory capabilities of Pleasure Activism. This investigation engages with the critiques of Pleasure Activism and provides some rebuttals as to why those arguments are flawed. Here, I reinforce why the “excess” argument against Pleasure Activism is a misunderstanding of the concept itself.

Substance use is a common argument used against Pleasure Activism as an example of dysregulated desire. In Pleasure Activism, every essay or piece on the subject of drug use specifically advocates for a harm reduction perspective. Harm Reduction is an approach to addiction work that accepts the fact that complete abstinence is practically impossible to expect, and thus any interventions should instead aim for a set of “compassionate and pragmatic approaches for reducing harm associated with high-risk behaviors” (Bowen et al., 2012; Marlatt et al., 2011). It is a perspective that prioritizes realism, and neither demonizes nor glorifies substances. This is an example that, of course, is focused on substance use, but it applies to all elements that give us pleasure, stimulate us, and that we risk becoming dependent on, whether it be sex and relationships, devices and short form content, or other unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Both amb and Lorde offer their opinions on this critique. While yes, the pursuit of pleasure is a subjective instinct, based on their definition, it is deeply connected to a sense of fulfillment within us that is directly connected to our individual and collective liberation. The idea that we can overindulge and become lost in excess conflates Pleasure Politics with addiction, twists it from a force of empowerment to a force we should be afraid of, and thus encourages us to distrust our internal sense of satisfaction.

It is one of the many excuses that is thrown in our faces as to why liberation is not possible for everyone. “Not everyone can be trusted.” “Some people always want more.” “We can’t give everyone what they want.”

The minority of rich oligarchs have already proven what things will be like if we allow the few to consume what they want. Why don’t we try to restore some equity by giving people what they deserve? What would that change? In what ways would that threaten the current establishment?

PA is not consumerism

A phenomenon that is not unique in the slightest but that I’ve noticed since writing a lot of my research two or three years ago, is how Pleasure Activism - like many black feminist theories of resistance - has been twisted to become reincorporated into the system that it is trying to protest against.

"Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare."

– Lorde, “A Burst of Light” (1988)

This is a very famous quote from Black Feminist Writer Audre Lorde from her text “A Burst of Light”. This collection of essays discussed her struggle against cancer as well as her organization work for LGBTQ+ rights and in Apartheid South Africa. This is a prime example of how the work of famous activists gets subsumed into the dominant ideology and depoliticized. All of the meaning of the quote gets lost as it is repurposed more and more, and each time the political intentions behind the sentence are decentered and it is reframed to be more aligned with the cause it is trying to critique.

The top review addresses how misrepresented Lorde’s writing has become.

Pleasure Activism, like the “self-care” movement, is founded by Black Queer Feminists as a radical way of caring for the members of the movement. When people get integrated into the work it is easy for the pursuit of justice to eclipse every need of the individual, which leads to burnout, conflict, and neglect of other aspects of their life. The importance of self-care in activist movements has been extrapolated to allow people who benefit from the system as normal to consume and market selfcare to others with a guilt free conscience.

This is one of the ways in which exploitative systems are able to neutralize resistance movements. By “taking the teeth out” – removing the aspects of the movements that are explicitly threatening to the status quo – they try to remove the impact that movement might have by oversaturating the definitions of the terms, miscommunicating the intentions, or shifting the ideals so it benefits those in power rather than those who created the movement in the first place.

Pleasure Activism is not consumption for the sake of it. It’s not even consumption with intention. Pleasure Activism is work. It’s work that aims to be enjoyable, yes, but it is still work. Navigating conflict, pushing ourselves out of our comfort zones, labors of love are all examples of Pleasure Activism, and none of them require expensive subscriptions, Amazon wishlists, or purchasing new products. It is not even a Marie Kondo approach to consumption: “If it does not spark joy, keep it, if not, discard,” is valuable to keep in mind, but it doesn’t reach the depth of feeling required to be defined as Pleasure Activism. Material items, while they can provide comfort and safety within certain measures, will not be the key to that sense of liberation, it barely even scratches the surface. If anyone tries to market Pleasure Activism, they have misunderstood the goal.

Pleasure Activism in Practice

So how do we access this deep recognition, and how can we use Pleasure Activism to begin to move towards these freedoms we deserve?

In my Instagram post, I include some examples of how I choose to incorporate Pleasure Activism in my life and in my work:

This is not to say that other forms of activism are less valid or effective. It is just a list of examples of how I choose to prioritize and structure activism work in my own life within my own means. This is not static or set in stone; it is flexible and changes as I learn and change.

Activism organized around arts, poetry, and music

I find that events centered around art can be much more effective in sharing ideas and mobilizing people as opposed to other structures, such as panels or teach-ins. The sense of inspiration that I feel when coming out of that space is so powerful, I am always motivated to create and write and share after participating in an open mic or a concert.

Carnival is a historic example of how dance and celebration disrupts the norm, and is a reminder of black pride and heritage that can not be ignored. Protests and marches are just as powerful; however, a similar physical presence can be created that is celebratory rather than a demand. They are just two different examples of the same tools with different impacts, and when employed, they can be even more effective. This Instagram video reposted by @moyo.afrika displays an example about how Carnival physically disrupts spaces, and forces the environment to accommodate black bodies.

As another example, in 2023, comedian and activist Ilana Glazer hosted her “Dance for Democracy”, in which all of the proceeds were given to Planned Parenthood and other pro-choice organizations to support access to abortion. In between DJ sets, Ilana spoke about the causes she was supporting and gave the spotlight to local council members and activists to share about their work and their organizations. You could get drinks and dance, as well as register to vote, get safe sex information, and volunteer opportunities, all in the same space.

Connecting through mutual joy and pride over shared pain

There is always space in our movements to heal from our shared experiences of oppression. It is the most critical work that needs to happen in order to move forward from the suffering that has been brought upon us by those who disempower and dehumanize us. Equally as important and often forgotten, is the value of bonding over shared experiences of joy. Celebrating our wins, enjoying our spaces, and indulging in the freedoms that we get to have now after previous generations have fought so hard for them. While it is important to remember that there is a lot of work left to do, and our rights are still constantly threatened to this day, our work must be reinvigorating and reviving if we are ever to survive this without burning out, falling into depression, or losing all hope.

Pride is a long-running example of how celebration can lead to liberation. Of course, most are familiar that pride began as a protest, and this displays how these two are inherently linked. Many younger members of the LGBTQ+ community at this point have probably gone through a similar arc of coming to terms with their gender and/or sexuality, attending Pride thinking they would find some form of solidarity, only to be confronted with floats of corporations with rainbow logos and problematic organizations. (This is, of course, with the understanding that not all people who participate in or attend the pride parade are like this, etc.) It is a common experience that previously radical gatherings no longer represent the liberation they demanded at the beginning.

“That is what happens when a queer aesthetic and attractiveness [are] centered above a strong foundational sociopolitical framework, and ideology, and identity.” User @convictjulie shares on Instagram. The movement begins to get subsumed into the dominant framework, so those who benefit can extract from it and neutralize the danger it poses, completely diffusing the core tenets of what it represented to begin with.

That is why Pleasure Activism advocates a return to the root needs of the community. It is not only about acceptance, about being tolerated, about being acknowledged in the dominant framework, about becoming more “normal”. It is about achieving our wholehearted liberation, and that stems from the belonging, the freedom, and the ecstasy we know we are able to feel.

In one of my earlier posts, (Searching For) My Bread and Roses Too, I cite some quotes from a podcast episode adrienne maree brown recorded with activist and organizer Nelini Stamp. They quote activist Helen Todd, who originally shared this line of people in protest wanting their Bread (practical, humanitarian, survival needs) and Roses (the pursuit of happiness):

“While she is discussing the issue of women’s labor rights, the sentiment could be applied to almost any movement. When people protest, they are not only doing so for human rights, the right to be safe, the right to be fed, the right to be healed when injured or sick. They are protesting for what humans deserve. Humans deserve to gather and celebrate however they choose. Humans deserve to show love and be loved by whoever they desire. Humans deserve to have access to beautiful art, witness incredible stories, perform from the heart, and be heard.

‘We want our Bread and Roses too,’ amb and Nelini say together.

Unity in the face of tragedy is deeply necessary. But it should not eclipse the human need to unite for joy, pride, and celebration. We have to unite around a shared cultural desire.”

– Holly Gregory, (Searching For) My Bread and Roses Too, Tools for Resistance (April, 2025)

There were many outtakes in this post where I attempted to describe the importance of not solely focusing on the suffering that takes place in the world. It can be a hard belief to try and advocate for, because the suffering in the world is so prominent and nearly impossible to reconcile with.

War, famine, climate change, hatred and bigotry, violence, all of these things are the reasons for which we protest with righteous anger and a hunger for justice.

Again, I want to repeat that I don’t want to make the argument that this is not a valid way to organize, that it isn’t a productive way to seek liberation, or even that it isn’t effective. It is absolutely effective. Black activist Assata Shakur said: “Nobody in the world, nobody in history, has ever gotten their freedom by appealing to the moral sense of the people who were oppressing them.” (While writing this, the news broke that she passed away in Cuba on the 25th of September after decades of exile.) What I am advocating for is that by organizing around and prioritizing shared experiences of pleasure, we can protect ourselves and our communities from the treachery of monotony, the threat of self-harm, and the negative effects of hatred and bigotry.

Unlearning supremacist perspectives and distancing myself from the scarcity mindset

In adrienne maree brown’s text, there are many pieces that center on detangling our true desires from the mire of supremacist and oppressive views that we inherit over time and over the course of generations.

“My body has the capacity to sense immense pleasure, and as I get older, I keep intentionally expanding my sensual awareness and decolonizing it so that I can sense more pleasure than capitalism believes in.” amb writes in the introduction of Pleasure Activism.

When it comes to any supremacist mindset, whether it is misogyny, racism, or homophobia, they not only colonize our physical spaces and bodies, but also our minds. It is hard to free ourselves from the limitations of these sinister forces if we can not imagine anything different. If our pleasure is still invaded by these oppressive forces, it is harder to reclaim our humanity, our agency, and our freedom.

amb dedicates multiple chapters to the ways in which we can decolonize our minds in order to open ourselves up to a more authentic relationship with ourselves and our pleasure. In one of these chapters, entitled “Liberating Your Fantasies”, they use the concept of fantasies, both inside and outside the bedroom, as an example of how supremacist mindsets can negatively impact our exploration of our own liberation.

“Fantasy,” amb writes, “becomes a safe space to desire things that we might never do or allow in real life.” (pg. 222) The potential and the limitations of our fantasies begin to be planted at a young age, influenced by the media we consume and the community we are raised in. This then impacts what we can imagine for ourselves and what we believe we deserve.

“We can get stuck in fantasies that don’t mature and politicize with us. We can get caught in fantasies that perpetuate things so counter to our beliefs and values that we feel ashamed of what we want, even as we find ways to get it.” (pg. 222) If our fantasies are colonized by our oppressors, what we believe we are capable of is limited by their imaginations of us. How they conceptualize us as women, as queer people, as people of color, as addicts, as housing insecure, as working class, as intersections of any or all of these things, infects our minds, our experiences, and thus what we can imagine and expect of our liberation.

“Some of [my fantasies] are rooted so deeply in my system that I’m not sure I’ll ever let them go… but I do want to be able to recognize what is mine and what isn’t, what should stay in fantasy and what is aligned with the world I’m generating.” (pg. 224)

When it comes to the scarcity mindset, it deals more with our relationship to others rather than our conceptualization of ourselves. Amb describes early on in her introduction that one of the intentions of Pleasure Activism is to distance ourselves from the perceived scarcity that threatens our attempts at generating more just futures:

“I have seen how denying our full, complex selves [...] increases the chance that we will be at odds with ourselves, our loved ones, our coworkers, and our neighbors on this planet.” (pg. 6)

Capitalism creates competition where there need be none in order to create conflict and disharmony between ourselves, and the system remains maintained. A manufactured scarcity is created in order to keep us fighting against each other, as opposed to those who hoard the wealth and resources. This idea immediately made me think of Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine, in which she describes a concept called Disaster Capitalism:

Our healthcare system is starved of funding so that efficient and compassionate healthcare is reserved for those who can afford the price tag. Housing is monopolized and then sold to the highest bidder, restricting people’s options for affordable housing despite the fact that thousands of places are left empty rather than allowing everyone to have a safe place to sleep. Food, clothing, arts and culture, transportation, entertainment, all of the facets of a functioning society are consumed by the insatiable forces of greed and then fed back to us with a lower quality at a higher price. All of our necessities should just be given to us because they are exactly that, necessities; but equally as important, our pleasure and enjoyment of life on this earth should be the intention of every structural system, regardless of whether we’re talking about a school, a workplace, an organization, a local community, a government institution, or a nation.

This is only one fraction of the ideas that Klein unpacks in her book – it could take another essay entirely to delve into it – but it is a well-researched example of how scarcity is primarily orchestrated by those with unprecedented control over our resources, our economy, and our governing institutions. This manufactured starvation immerses us in the sensation of lack, but it is deeply unnatural, and with intentional change, need not exist entirely. (To read more about this I highly recommend this Guardian article entitled Naomi Klein: How Power Profits from Disaster.)

“Pleasure Activism asserts that we all need and deserve pleasure and that our social structures must reflect this. In this moment, we must prioritize the pleasure of those most impacted by oppression. [...] Pleasure activists believe that [...] we can generate justice and liberation, growing a healing abundance where we have been socialized to believe only scarcity exists.” (pg. 13)

Conclusion

Pleasure Activism is not the only method towards resisting oppression. It is just one of the approaches that I have found makes me able to live with authenticity and integrity.

In open discourse, especially with short form content the way it proliferates now, it is common that when a point is made, people begin to pick apart everything it isn’t saying. Just because I am putting forth and reinforcing the importance of Pleasure Activism to the framework of Tools for Resistance, does not mean I don’t simultaneously advocate for boycotting, voting, protesting, sit-ins, panel discussions, or strikes. It is just the underlying philosophy that I choose to align with when it comes to navigating how I want to engage in resistance.

Pleasure Activism is difficult. It is awakening to the multitude of ways in which our oppressors limit and lie to us for their own gain. Pleasure Activism is challenging. It is realizing that your mind, your thoughts, and your relationships may still be colonized by the oppressors. Pleasure Activism is complicated. It is realizing that you have to confront issues of substance abuse within yourself, domestic abuse within your home, verbal abuse within your workplace, exploitation at multiple intersections… and yet still continue to persevere with pride and integrity. It is choosing life rather than falling under the weight of guilt and shame that threatens to burrow within and consume us. It is choosing to participate in the resistance when there seems to be so few options left to us.

If I’m sounding a bit pious in regard to this, it is because it is not only a philosophy for organization and activism, it is also a bit of a religion for me.

It serves as a list of morals and goals of how to live my life and how to overcome suffering, or at least mitigate the effects of it as much as possible. People often turn to religion during difficult times in their lives. Pleasure Activism has helped me to overcome encounters of depression, addiction, isolation, and violence, all of which come from deeply personal experiences and from shared experiences of oppression.

References

brown, adrienne maree. (2019). Pleasure activism: the politics of feeling good. AK Press.

Bowen, S., & Vieten, C. (2012). A compassionate approach to the treatment of addictive behaviors: The contributions of Alan Marlatt to the field of mindfulness-based interventions. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(3), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2011.647132

Wupperman, P., Marlatt, G. A., Cunningham, A., Bowen, S., Berking, M., Mulvihill‐Rivera, N., & Easton, C. (2011). Mindfulness and modification therapy for behavioral dysregulation: Results from a pilot study targeting alcohol use and aggression in women. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20830

Lorde, A. (1988). A burst of light: Essays. Firebrand Books.

Newman-Bremang, K. (2021, May 29). Reclaiming Audre Lorde’s Radical Self-Carereclaiming Audre Lorde’s radical self-care. Refinery29. https://www.refinery29.com/en-gb/2021/05/10499036/reclaiming-self-care-audre-lorde-black-women-community-care

Klein, N., & Fenton, K. (2025). The shock doctrine the rise of Disaster Capitalism. Penguin Random House.

Larry Glass, By, Larry Glasshttps://www.yournec.orgLarry Glass is Executive Director and Board President of the NEC, Glass, L., & Larry Glass is Executive Director and Board President of the NEC. (2022, November 30). Larry Glass. NEC. https://www.yournec.org/pleasure-activism-finding-joy-in-doing-the-work/

Links

Comments